Teenage years – filled with identity crisis – changed Hassani’s perception of who he was. He didn’t want to sing anymore. Singing was too sissy, too effete. He wanted to man-up, be masculine and be every other stereotype perpetuated by society about men.

Sitting on a sofa he had dragged into the middle of the large living room, and directly facing me, he described himself as “effeminate emotionally” but not physically, “just a little softer than most men. It’s how I am. It’s nothing to be ashamed of”.

Hassani had been singing since he was seven years old, his voice finding home in the church choir, but rap was what he started off his music career with, hiding his high octave voice and shy disposition behind the aggressive shelter it(rap) offers. For one who tethers on the edge of dandiness and sings about love in an almost feminine voice, it’s hard to believe he was once a rapper.

When he pursued a career in rap under the stage name, Rico Slim, Hassani wasn’t true to himself and he knew this and others could tell that he wasn’t being his real self. So when his alternative songs began to enjoy mainstream popularity and airplay, Hassani’s friends, Skales in particular, called him up to hail him for finally embracing his true nature.

With his style of music that is non-threatening, devoid of aggressiveness and a physical appearance that bellies strength, Hassani represents an often-ignored class of young male Nigerians that have no street credibility, abhor aggressive behaviour that society often expects of men, are geeky, socially awkward, and constantly fighting off waves of low self-esteem.

“I grew up a geek really. Between math, physics and my big glasses… I wasn’t a good-looking guy at all,” Hassani says. “I wasn’t socially cool at all,” he adds with a brief shake of his head.

He is so anti-social that he avoids staying backstage or coming early to gigs where he must perform with other artistes. He is almost unsure of how to interact and mingle, so he comes at the exact time he is expected to (or hides out somewhere), performs and leaves immediately.

“When I go for shows, it’s from my car to stage and from stage to my car. I’m going back home.” It isn’t snobbery. Hassani is afraid and unsure. He isn’t accustomed to being “the cool guy that when I walk in people stare at me”.

Hassani says he only began to find peace when he found himself; appreciating his differentness and finding peace in knowing that he lacks – and probably will never have – the masculine bluster that is marked by machismo and a need to dominate, loudly.

Hassani’s affinity with love

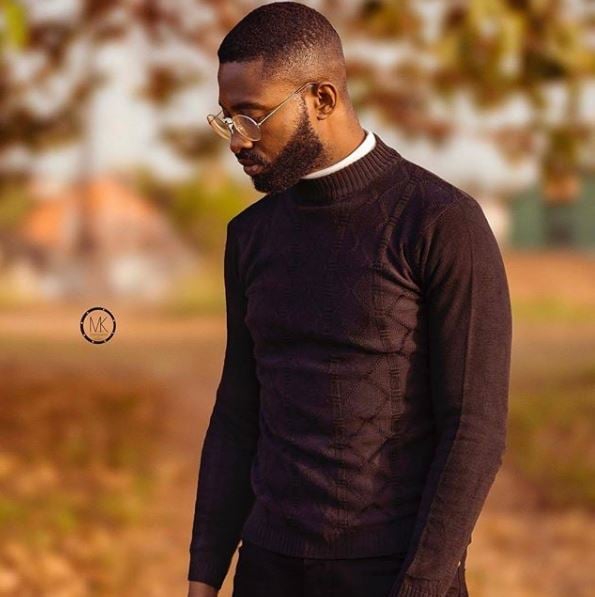

Hassani is almost always dressed as if he’s the top model of an Africa-inspired Tom Ford collection. His well-tailored clothes – that tastefully combine Ankara prints with corporate designs – have redefined how an African gentleman should look, while also building and solidifying Hassani’s brand.

But right now, Hassani — dressed in a black t-shirt paired with black slack pants with red Ankara print running by the sides and a blue flip-flop — is anything but camera ready. He is recovering from a bad bout of malaria, which for the past two days has kept him stuck at home.

“You came to write about the African gentleman that has malaria,” Akah Nani, an actor and media personality, – who, I figured, is one of Hassani’s close friends – joked later when we met indoors.

Hassani jovially warns me not to mention how tired he looks and the fact that, although it is almost 6pm, he is yet to bathe. I tell him that I will consider it.

When Hassani speaks, his eyes widen behind his thick lens, acquiring a dramatic glint like a glowing orb. His sense of humour is whimsical, almost robotic and leaning towards self-deprecation – and this is surprising considering how serious he dresses, looks, sings and tweets.

His songs are “soulful,” riding on a repetitive beat with minimal baseline, adorned with masterful acoustics. Through his lyrics, Hassani pours his heart out to the listener, inviting you to see love as he does; letting you know that no matter what, love could be a beautiful thing.

Although Hassani isn’t the first Nigerian artiste to celebrate the idea of love on songs, his approach is certainly different. For long, Afropop, — constantly evolving till it became a lyrical cesspit that is resplendent with catchy words and wit, but lacking in depth — has celebrated the idea of a love affair in a way that glorified misogyny, tethered on the edge of encouraging rape and sexual violence, and praised the female anatomy in ways that are far from tasteful.

“Ninety percent of my extended family are girls. I don’t know how that is,” he says, framing his face with his hands.

As a child, he witnessed them fall in and out of love, making bad choices in romance and love. So, when he sings of love, in a way, he is singing a long overdue love song to the broken hearts of his sisters and cousins, who “were in the worst relationships known to man”.

Hassani admits that he has no first-hand love experience. Instead, the Port Harcourt-born singer channels the experiences of women he

grew up around, singing songs that would mend hearts broken in the past.

“When they come back from these dates they’ll be saying ‘oh the guy is nice but he should have done this’ or ‘he should have this’ or ‘why didn’t he say this?’ From this, Hassani says, he learnt what a woman wants in love and romance.

Hassani thinks his brand of music is “pure and honest” because the inspirations behind his lyrics are pure and honest. If he is addicted to anything, then it is to watching couple engagement videos on YouTube.

It’s from there that he gets the energy he feeds into his song – painting a near-perfect picture of love. “I feel like that’s one of the most vulnerable, pure, honest moments between two people ever,” Hassani says of engagements. “And in those moments, I get to tap off the emotions. I get to draw from those emotions. Put it in a bottle and go to the studio.”

‘Men are my biggest fans’

Hassani says his music is a redemption of sorts for men. But then he counters, saying, “not really redeeming. It’s two ways. Honestly, some men want to be the nicest guys. Some men want to say the nicest things. But they don’t know what to say and how to say it. Let my song help them. You know what I mean? On the side of the females, if they don’t have any man to say these things to them, let my song say it to them.

“That’s why a lot of people tell me that they always replay my song. To remain in that bubble. They tell me ‘Let me just be inside this Ric Hassani song now to just make myself feel that I’m in love, loved – like I’m in a relationship even if I’m not in one’.

“The funny thing is: most of my fans are guys.”

Two days prior to my visit, Hassani’s team ran a web analysis to look up trends on his fan base when they made the discovery; “It’s 65% men and they live in Lagos”. A radio presenter, he says, once told him that more often than not it is men that call in to request his songs.

Nigerian men are low-key romantics, Hassani opines.

A man on his own

Hassani is the last child in his family and a five-year age gap stands between him and his immediate elder sister. This significant difference, Hassani says, afforded him the opportunity to live two lives: theirs and his. Learning through their mistakes; taking in those indirect lessons whilst finding his own path and rhythm.

No matter what, this never stopped him from learning the difficult lessons about life. By 2010, aged 20, Hassani started shuttling between Port Harcourt and Lagos, the bustling city where people come in search of wealth and/or fame.

It would take seven years before his music would find home on playlists and, eventually, in hearts. Hassani, alongside a couple of other young hitmakers, slept on the floor of a producer’s studio, hoping that their next studio session would be the one that brings good fortune their way.

The first time his song was played on MTV, Hassani had no idea. He had made no marketing effort to get the song played on a major channel, claiming that the station had to go get his song from YouTube, airing free to millions of people.

Is Nigerian music at a tipping point?

But for the occasional use of Nigerian references in his songs and his identity as a Nigerian, Hassani might as well be an artiste from anywhere in the world. This global appeal presents a problem of sorts, seeing that we live in a society that thrives on classification and labelling.

Where do we place Hassani in Nigeria’s music scene?

His debut album, released in mid-August, was met with delight – from reviewers, musicians and fans alike. His steady crossover into the mainstream — with a sound that totally deviates from the pon pon sounds that have dominated the airwaves this year — is no mean feat and it signifies that, perhaps, the music appetite of Nigerians is diversifying, opening further to new styles and approaches that have stayed in the underground, ignored for years.

In the context of differentness, Hassani says he identifies with the late Fela Kuti.

He explains: “The idea behind Fela is that he was a nonconformist. He made music the way he wanted to and he said what he wanted to say – which is politics and all those things he was talking about. Me, I am a nonconformist. I make the kind of songs that I want to make and talk about what I want to talk about, which is love.

“Ideologically, we are the same kind of artiste,” Hassani says, adding that “but sonically, we are not because I make pop-bubble-gum music.

“I am making this kind of music because this is what I know how to make. I am not making it because I think this is what will sell or this is the future.”

The power of being alone

Hassani and I are done talking; he rushes upstairs to dress up quickly. Outside, the sun, after hours of blanketing Lagos in sweltering heat, has finally gone to rest, paving way for the moon and the coolness it brings. Hassani, who is heading to a surprise birthday party for M.I. Abaga, offers to give me a lift. I accept.

Hassani has been through the worst: he’s been so broke that he couldn’t afford to attend the shows he was invited to. He fell into depression between 2013 and 2014 because his career after so many years was barely above ground. Gentleman, recorded when he was about to give up, would become his breakout song.

But right now, sitting in a car parked in front of a one-story duplex he recently moved into at Ajah, Lekki, Hassani is trying to process why his fuel tank is near red. He calls a friend who drove the car earlier. This friend explains the empty tank and ends with: “you know I no fit do you bad thing.”

Hassani harps on the importance of forgiving people who are good to you despite their little failings – like the friend who drove his vehicle last.

“Forgiveness isn’t for the other person. It’s for yourself,” he says. Hassani has moments like this: where he launches into a motivational speaker and making scriptural references as if he is a younger Sam Adeyemi.

He is aware of how he is perceived and he is wary of sounding too “deep”. On one hand, he is proud of the brand he created and on the other, he is worried that people may get lost when he speaks. So, he punctuates the tail-end of his sentences with “you get what I mean?” and “you understand?”

By now, Hassani is nearly an hour late to M.I’s birthday. “M.I is an amazing person,” he says, steering the car to a stop before a traffic light. He looks at me over the rims of his glasses before pushing the thin frames up his nose.

He hasn’t always known M.I – he can’t even explain how they got to know each other – but their relationship grew fast from nowhere, with M.I serving as a mentor of sorts, who acknowledges the brilliance of Hassani’s brand and the greatness he could achieve.

M.I wanted to sign him to Chocolate City and although Hassani considered it, he backed out of after realising that one of his strengths was the mystery of being alone, in his own corner.

“There’s power in being alone,” Hassani says.

Hassani turned down M.I but has remained good friends with him, describing him as one of the people in the industry who look out for him. And it’s not just M.I, it is the entire Chocolate City Music group. They come out to support him at his shows and even send a few paying gigs his way every now and then. Hassani isn’t sure what he did to deserve the love.

After we had bought petrol at Ajah roundabout, Hassani starts talking about greatness. He name-drops entertainment figures that have broken glass ceilings – Oprah, Steve Harvey, Jay Z, Beyoncé, Sam Smith. The singer says he spent time watching and re-watching their interviews till he concluded that greatness can never be accidental, but rather, is inborn.

Hassani sees such greatness in himself and he appears to be on a journey towards achieving it.

Copyright 2025 TheCable. All rights reserved. This material, and other digital content on this website, may not be reproduced, published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or in part without prior express written permission from TheCable.

Follow us on twitter @Thecablestyle

Let me look out for this guy. This write-up is deep. I must lookout for this Hassan guy

You are a fantastic writer. Absolutely brilliant.