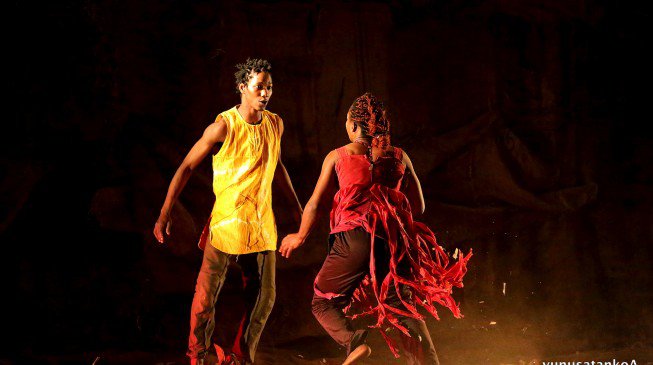

Words and Pictures: Yunusa Abdullahi

It was a night in which Qudus Onikeku held his audience spell bound through an hour of what seems like a Shakespearean play. The atmosphere was lightening; the set not what you see in a normal Nigerian dance drama or choreography.

The audience at the prestigious National University Commission Auditorium, Abuja, on Sunday night itself was seeing such a performance for the first time. It was full of passion, emotion, some cold some desolate, some totally cathartic. From Berlin to Lagos and Abuja, the story is the same: same questions, same responses.

The violent nature of the production leaves much to be desired, but Qudus is not phased by the questions. According to him, whenever he is asked why he created a work so violent, his reply has always been: “I want to dance about peace, but since the world denies me of such proximity… with beauty from all around me, out of the sorrows and tears, out of the discordance and the screams, one could extract art works that are essentially beautiful, meditative and contemplative.”

But Qudus is not alone in trying to be existentialist. The theatre world has always been awash with realism which simply suggests portraying life as real as possible.

The term got prominence as its elements were in contrast to the prevalent Elizabethan theatre techniques, as against the minimalist or representative sets in Elizabethan style.

Realism style uses elaborate and real-life depiction (props, furniture) in set design.

Also, in contrast to the loud, flowery declarative speeches, directed towards the audience, realism actors speak normal, everyday conversational pattern while facing each other.

To an extent, realism theatre also prefers picking up stories from normal, everyday lives and less of fictional fantasy world.

There was a deliberate effort by the proponents of this new school to break with traditional subjects of artistic expression such as mythological and religious subject matter in favour of more down-to-earth subjects and themes: working class people, slice of life scenes, the grit and texture of city life, etc.

In theatre, realist works are characterised by natural speech, naturalistic portrayal of social issues of the day.

The early realist artists in Europe included Ibsen (Norway), Bernard Shaw (Ireland) and Chekhov (Russian). Their plays depicted themes of contemporary social and political themes. Another exponent who is considered to be one of the pioneers of realism was Konstantin Stansilavski. His “systems” acting style probes his actors to recall their “affective memory” to portray real-life character’s emotion.

Qudus continues in a response to a question on the attendant violence in his dance: “Our world is a world of causalities and like so many survivors, I still jump at the sound of a loud noise, sights and sounds and smells – anything can unexpectedly take us to those memorial spaces, where we’d rather not go.”

Qudus is so cerebral he thinks and talks beyond his age. He is philosophical, he is confident and has the ability to throw in the odd joke in his conversation.

He believes there is no need denying the fact that the world is all about conflicts, wars, starvation, hunger, violence against children and women. The world is about rape, torture, crashes and assaults.

So instead of denial, his cathartic philosophy takes him on a “journey”, that journey is what ‘”We Almost Forgot” intends to lead to.

Qudus silently and subtly idealises on the principles of a silent ‘revolution’ through dance, a system popularised by Vladimir Lenin and his confidants.

Qudus believes and understands how non-verbal dance could convey ‘revolutionary’ messages to the people more effectively than the spoken word.

His artistic philosophy tries to purge the contemporary dance of what Yakobson the Soviet choreographer refers to as “artistic stagnation” and “anti-creative quagmire”. He therefore wishes to modernise to communicate ‘revolutionary’ changes.

He wants his audience to empathise more, to imagine those joyful moments, moments of love, feelings of shared grief and love.

He ended by warning us that there is a day after tomorrow where all mortals must account for their infractions.

Copyright 2024 TheCable. All rights reserved. This material, and other digital content on this website, may not be reproduced, published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or in part without prior express written permission from TheCable.

Follow us on twitter @Thecablestyle