BY ABIODUN ADENIYI

Edited works are most times high-quality works. The reason is that they are a conflation of intellectual resources. In them, we have an assembly of writers approaching a theme from different perspectives. They then deepen the scope of approaches, the breadth of analysis and the width of understanding. Works that are edited fall within the modern appreciation of joint work, especially Journal articles. Joint research is becoming the fad, in highly rated journal articles, for the supposed aggregation of efforts, in the bid to capture the all-pervading essences of human activity.

In the case of a book, we have authors submitting copies and then we have several other writers editing them, in line with the blind, peer review mechanism. Some of the copies are also joint, adding to the separated spice of inputs. What it translates to is the densification of ideas, the compaction of notions and the signification of new trends from a multileveled outlook. Engaging books like this, is, therefore, an opportunity to savour the outputs of writers from different flanks, a variegated worldview and differing socialization. The reader is then exposed, only from one piece of literature, to some fulsome details about a subject having been produced by a range of experts.

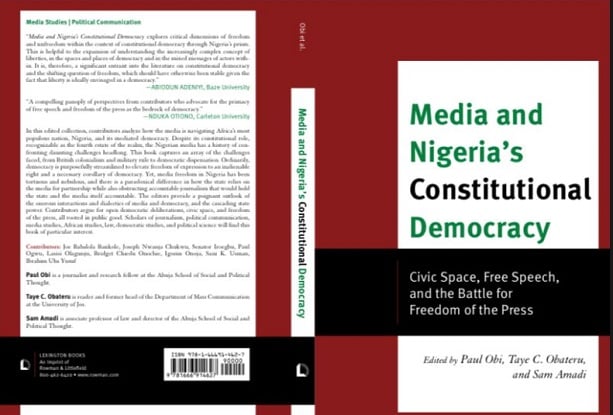

That is the lot of the book we are presenting today, entitled “Media and Nigeria’s Constitutional Democracy: Civic Space, Free Speech, and the Battle for Freedom of the Press”, edited by the trinity of Paul Obi, Taye Obateru and Sam Amadi. It is a 162-page collection, divided into ten chapters, covering different subthemes, pointing at the core theme of constitutional democracy and free speech.

The book begins with an introduction inviting us to the past and contemporary struggles of the press with the authorities over the right to free speech. The introduction uses contemporary and past instances of campaigns to demonstrate how the state has tried to muffle the press, forgetting that the press is the reflector of views in advance of actions for growth and development.

Freedom, it suggests, is a basis for progress, given that it enhances fulfilment, leading to optimization of potentials and then progression, leveraging on the evident display of the people’s possibilities. Caging the press translates to caging the thoughts of the people. And when thoughts are suppressed, ideas are buried, evening up to stasis, and then the dearth of understanding and knowledge for development. The chapter signposted the destination of the book, readying the reader for the rigorous work just ahead.

The chapter after comes with the part of Amadi who disputes notions around the dawn of the argument on the Freedom of the Press, from the colonial times to the immediate post-colonial period, before zeroing in on present times. In his input, entitled “Assessing the Legal Protection of Freedom of the Press in Nigeria’s Constitutional Democracy” his legal background formed the basis of his didactic exploration, helping him to introduce arguments around the press and constitutional democracy, the press and fundamental human rights, the place of the bill of rights, freedom of expression, and shades of judicial interventions. He concluded by regretting ambiguities in the constitution, the decline of standards in the interpretation of the law, and the unlikely realization of the envisaged freedom, save the judiciary becomes much more responsive to the challenges of protecting the rights of man.

Paul Obi stepped in with his article entitled “Media Censorship of Nigerian Presidential Elections? Navigating Candidates, Campaigns, and the Monetary Democracy Theory” where he was laborious in his evaluation of the relationship between the state and the media, and how they have fared in Africa and the global South. Obi suspected censorship of media in the course of illiberal elections, through subliminal but effective mechanisms, because of the open claim to democracy. A fan of Keane’s Monitory Democracy Theory” he implicated, from an investigation, deliberate and subtle measures of control, which deadens the capacity of functionaries, while calling for some form of countermand through determined investigative reporting.

Taye Obateru came next, changing the narrative by focusing on ethical matters, in “Who Watches the Watchdog? Ethical Interrogation of Self-Censorship in the Nigeria Media” Obateru provided a clear picture of the shades of unfreedoms in the media, drawing parallels from across the world, before harping on the productivity of professional ethics. To the writer, the question of self-censorship is significant enough to determine the efficiency of the practice. This, he added, can be effectuated through subscription to ethics, which is often the bedrock of valuable proficiency.

Bridget Onochie, Lasisi Olagunju, Paul Ogwu and Paul Obi then stepped in with their piece on “The Shrinking Civic Space: Journalism Hazards, Risks, and Contemporary Media Resistance to Censorship in Nigeria” wherein they x-rayed the many instances of the clampdown on the press, whether on the traditional, new or on the social media. These, they saw, as closing the spaces of interaction, the public sphere of exchanges and the spaces of ideation. From the death of Journalists to harassment and imprisonments, they railed at the unpleasant experiences, before clamouring for freedom, through levels of media advocacy, amongst other mechanisms.

For Igomu Onoja who joined the arguments in “National Broadcasting Commission, Nigerian Press and the Media: Regulation in the Age of Information Fluidity”, the writer highlighted the importance of regulation, but not at the expense of a vote for ethics, peer review, and the permission of independence. Government interventions should be marginal, if at all, given the tendency to overdo, and the likelihood of this affecting the creativity and ingenuity of the media.

Another article “Walking the Tightrope of National Security: Interrogating Public Interest versus the Politics of Media Censorship in Nigeria”emanated through Ibrahim Uba Yusuf, Senator Iroegbu, and Sani K. Usman, where they interrogated questions about National Security, National Question, and responsibility of the practitioner to the nation-state. While charging the journalist to be moderated on sensitivities, they also asked authorities to be no less efficient in engaging the media practitioner.

The subject of the moment arose in Chapter 8, “Technology, the Internet. Social Media, and Online Free Speech in Nigeria”, as examined by Joseph Chukwu. This chapter was seminal in evaluating the evolution of media technology and how it has shaped the world we are presently in, by redefining social, economic and power relations and how it has triggered citizen participation in statecraft. It captured the new times, providing a breather of sorts to the density of expositions on traditional media in chapters prior.

Joe Babalola Bankole picked on Information ministers in his article “Deconstructing the Fourth Estate Ideals and the Quest for Free Speech: A Study of the Speeches of Nigeria’s Minister of Information on the Role of the Media (2015-2022)” Compact, breezy and at once impactful, the chapter was investigative on how ministers charged with the information portfolio have fared, in addition to their places in the determination of freedoms. Using relevant examples, Babalola regretted evidence of curtaining media freedom in the guise of dealing with fake news and thereby limiting the essence of democracy.

The editors concluded with an invitation to scholars to identify areas uncovered, for further studies, while re-emphasizing the nobility of press freedom, the importance of growing its culture and its intrinsic essence in social, constitutional and democratic evolutions. Overall, the book is what we can call a collectors’ item, indeed an excellent bid to couple scholarship and journalism thoughts in one loop, if you look at the blend of writers on parade

Regardless, it is slightly let down by inadequate references in some instances, while in others, the references were listed, but there was no evidence of consulting them in the body of the articles. Though grammar is largely standard, more because the writers are practised, some articles presented as academic pieces, were riddled with journalese.

These are however not enough to diminish the book’s credentials as an outstanding work, and a unique, unexampled contribution to the body of knowledge, the endless conversations on the place of the press in a constitutional democracy. Great work by great writers, it therefore remains. Congratulations, Paul and company. More grease.

- Abiodun Adeniyi, Professor of Communication, is the Dean, School Of Post-Graduate Studies, Baze University, Abuja.

- ‘Media and Nigeria’s Constitutional Democracy: Civic Space, Free Speech and the Battle for Freedom of the Press’ was edited by Paul Obi, Taye Obateru and Sam Amadi

Copyright 2025 TheCable. All rights reserved. This material, and other digital content on this website, may not be reproduced, published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or in part without prior express written permission from TheCable.

Follow us on twitter @Thecablestyle