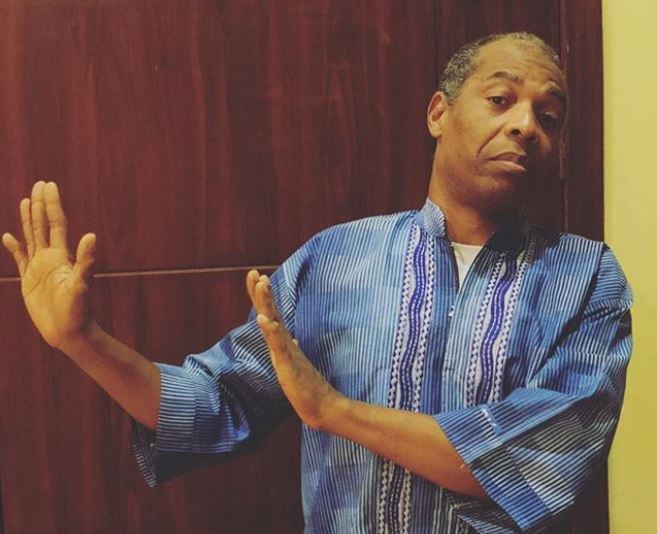

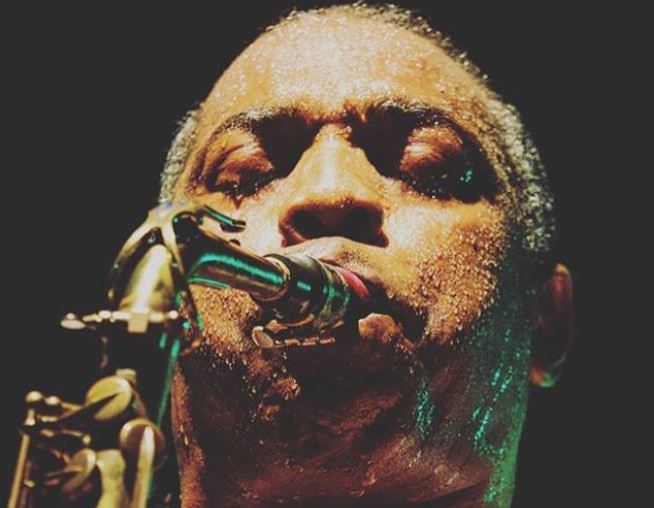

That Sunday night when the air smelled of rain but not a drop came down, Femi Kuti, a shivering vision draped in blue disco light and theatrical fog, wailed about corruption on the New African Shrine stage.

He was debuting his new album: One People, One World. He is like a preacher, addressing a loving crowd of eager believers. At different points, Kuti stops singing and embarks on a five-minute monologue about everything: the difficulty of music promotion, being underestimated, sex (coated in metaphors of “action” and “shoki shoki”), food, and corruption.

The crowd laps this up, cheering him on, patiently waiting for the music to come back on.

For Kuti, music has never been about fame or fortune. It is about passion and love. “Musicians are just a medium that higher forces gave a gift and put in place to be used for inspiration. You start at the age of five and do it till you’re dead,” he says.

Every week, the Shrine is packed with people looking to be inspired and entertained. Kuti says it is his duty to play music that will bring joy and make people forget about the troubles and pains in their lives.

That night, before the sky decided to swallow the rain it promised, Kuti closed the show early, sometime after 11pm, something about going home to his daughter who had just had a surgery.

Today, when the sun holds Lagos in a hot embrace, almost two weeks since that Sunday, Kuti and I sit for an interview in a dressing room at the Shrine.

We are seated under the sign that says: “Go now, why wait?”

Kuti, 56, is ageing gracefully. His hair, cut low and thinning, is a fresh maze of black and grey, attesting to his age. He is wearing a black t-shirt and ankara trousers, holding a trumpet in his left hand.

I am at first convinced that he is uninterested in speaking with me, eager to get the interview over with. He sits on the edge of his seat and our eyes do not meet for the first two minutes. But we soon fall into a rhythm, with him doing most of the talking, occasionally breaking his words to let out a laughter or to ponder a question asked. He is introspective but engaging, and with time, open and endearing.

Several times during our discussion, Kuti would allude to the fact that he is easily misunderstood.

Every day, he says, a part of him melts from the love his children profess for him. Even though Fela never said ‘I love you’ to him, Kuti makes sure he says it to his children.

“What is important for me is when my children come to me and say, ‘Daddy I love you.’ Ah! This kills me! And there is nothing anybody can say that will stop my children from saying this to me once a day, at least,” Kuti says, his eyes holding mine, a smile pushing at the sides of his lips.

“Many people don’t understand. Many people their parents find it difficult to say, ‘I love you’. My father never told me ‘I love you.’ He thought it was too western.”

Femi: Fela’s experiment

Femi Kuti was Fela’s experiment. A living proof to the world that what preached so passionately — Pan-Africanism, anti neo-colonialism — were not just mere theoretical rants of an idealistic musician.

“My whole life is an experiment which I’m still living and will die so,” he says, accepting that he lives a life based on experience and constant experimentations.

Kuti isn’t educated. It is a fact that he openly admits, even as he encourages everyone to get an education. Fela wanted to prove, through his son, that one didn’t need an education to succeed.

“Do I talk like someone that is not educated?” Kuti asked. “But I am not educated. I come from a good background and I have done a lot of reading and know my job.

“He (Fela) was right in some ways but very risky. I succeeded and I have had experiences. It has taken me 18 years now to play the trumpet, to get to a comfortable point. Probably take me another three to five years to become what I call master.”

Kuti questions everything, he approaches life with an intellectual curiosity that was borne out of a need for enlightenment and knowledge. Maybe it was because of his father (in fact, father and son bonded over books so much so that Fela took to calling his son ‘professor’). Kuti started to find biases in books and discuss them with his father. This freedom to explore and question taught Kuti to have a mind of his own.

It is difficult to explain – or even explore – the relationship between father and son. Even Kuti sometimes runs in circles when talking about his father, conscious not to say the wrong thing, to avoid stirring murky waters.

“My father wasn’t conventional,” he says, pointing out that when he talks about his complex relationship with Fela, a lot of people won’t understand.

Prophet without honour at home

When he left his father in 1986 to start off on his own, the media and the public “crucified” him.

Carlos Moore, Fela’s authorised biographer, in an updated epilogue of the book Fela: This B***h of a Life, described the estrangement this way: “[Femi] a composer in his own right, the budding musician was on his own journey of creative self-affirmation; father and son no longer saw eye to eye on the most basic issue – music. In 1986, Femi walked away from his ten-year membership in Fela’s band, and set up his own Positive Force; father and son would remain estranged for five years.”

Kuti decided to leave Nigeria to make his name abroad where he now enjoys a larger fanbase than in Nigeria.

“I was making money outside here. Nobody wanted to watch my concert here. I played ‘wonder-wonder’… and even when I did ‘wonder-wonder’ my father was alive – they gave credit to him that he must have written it for me.”

After his father’s death, Kuti released ‘Beng Beng Beng’, an instant hit that had Nigerians believing in the authenticity of his genius.

Records released before this had gone unnoticed in Nigeria. And in recent times, people are beginning to take interest in his music.

“Probably because of Chocolate City in Nigeria and they have a good footing here and are promoting it,” he says.

For much of his life, Kuti – who has composed over 130 songs and has been nominated for four Grammys – has been ceaselessly compared to his father, his works sometimes dismissed for lacking the radical, daredevil heft that Fela’s had.

On that, he says: “My father was direct, should I be direct in every song? For me, it’s even boring. Do I eat eba every day?”

Over the last 39 years, Kuti has learned “to leave people in their stupidity. Everybody learns before they die”. He mentions a recent review of his song by a 31-year-old critic, (who described his song as politically ‘vague,’ angering Kuti’s first son to go on Facebook to point out the error of the critic).

There is a long trail of media interviews where Kuti has taken the pain to point out the difference between him and his father, arguing that he is his own person and that his approach to music, too, is different, insisting that he is uninterested in filling his father’s shoes.

Equal opportunity for everybody

When he speaks about equality, his face lights up and his voice becomes increasingly animated.

He believes in equal opportunity for everyone. Like the elite, children of the poor deserve an opportunity to attend good schools, have the best education and good social privileges, he says.

Kuti had adopted four of his son’s friends, putting them through school and raising them as his. These children – now married, graduates or about to graduate – were from poor homes but they did better than Kuti’s son in school.

His phone rings – a jarring, shrill ringtone. “Let me answer this quickly,” he says, picking up the phone. About 30 seconds later, he is done with the call and continues, but it rings again ten minutes later, cutting him off mid-sentence. Kuti mutters “heeeyi,” picks up the call and promises to call back.

He argues that equal opportunity is for everyone regardless of class, gender or identity. “I cannot discriminate against my girl children over the male,” he says.

“I will never give the male child more than the female. I will bring them up in a very African way: you the male must look after your sisters.”

But asking his male children to look after the females doesn’t mean men are “brainer than women”, even though one sex possesses more physical strength than the other. This physical strength, Kuti believes, should be used by his sons to protect his daughters, the African way.

“We must help each other. It’s like a partnership… even, there are some females that are stronger than men. Some men are very weak. I know a girl when we were going home one day, she just carried two 50 litre kegs. I said ‘yeeee!’” Kuti shouts, lifts up his hands and lets out a guffaw. He pets down his thigh, laughing, the sides of his eyes drawn together with laugh lines.

“Macho rubbish” and king women

“There are some strong women. Ah ah! What about my grandmother? My grandmother was strong,” he says, matter-of-factly.

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, his grandmother, was a woman ahead of her time. She organised women in Abeokuta, Ogun state, took an active role in politics and even deposed the Alake of Egbaland.

She “drove him out of his kingdom. No male could do that. This discrimination of gender is not African. It has never been African. African women rose to be kings. Not queens, kings. They ruled empires in this continent. And when they give them chiefs, they didn’t give them chief of the female gender. Your chief is a chief.”

Kuti says men are prone to be heady and unable to see the finer details the way a woman would. Before he takes a major decision, he consults his elder sister – and, before they passed away, his mother and younger sister.

Over the years, Kuti and his sister, Yeni, have grown so close that he could easily imagine her advice to whatever situation he presents to her. The women in his life gave him advice from “a very sane perception. So I don’t need to be violent or angry. I can be very diplomatic and I’ll still get to where I’m going.

“I will not say I am a feminist. I will say I am human. It’s not about gender. It’s never been about gender. It’s Europe, it’s colonialisation that brought all these complications into our lives.”

When Kuti’s mother died, he was so grief-stricken that “the world moved on” without him. His world went blank and he was lost in his pain and sadness.

“Even if you say, ‘hey, Femi, how are you?’ I didn’t hear. I didn’t hear for many months. I couldn’t reason for many months. When my younger sister died, my life was a misery. My daughter just had an operation and we all thought she might not survive. My life closed.”

Speaking of masculinity and its toxic nature, he roundly refers to it as “macho rubbish.”

Even though he blames the West for many of Africa’s problems, he readily concedes that “all these race wars are there to make us more divided. I have a lot of European and American friends. I don’t talk to them differently. I take them from a human point of view because I have learned in my lifetime that there are many terrible Africans who have ruined my life at different times”.

Why is Africa the way Africa is?

One People One World is his tenth album and it has a global outlook. On the album, Kuti speaks to a world audience, using his musicianship as a platform to call out social issues and government failures.

“Yes, my orientation is Pan-Africanist, African, but I think globally and I try to address world issues these days but still focusing on Africa,” Kuti explains.

At its core, the album is optimistic – although it is interspersed with some angry outbursts, where Kuti decries the state of Africa and corruption. But his approach nowadays is to ask more questions.

To answer a troubling question: “Why is Africa the way Africa is?”

Most times, the answer isn’t forthcoming so he answers his own question: “Africa is the way it is because of slavery and colonialism”.

Kuti, who is about to embark on his European tour, asks: “Do you think Africa can just snap out of this problem?”

On the first track in his album, Kuti sings that Africa will be great again. And on the last track, in a mellow voice riding on a slower rhythm, he says “one day the people will raise” and “change is on the way.” He believes in this, yet, keeping to his realistic view, he doesn’t think Africa will achieve this greatness in his lifetime or his children’s.

“If I really want to be frank, maybe in a hundred years,” he says.

“What I am trying to do with my music is to take us back to start thinking. It will take a long time, not in my lifetime.”

The album has a funky feel that is reminiscent of James Brown. I ask him if Brown had an influence on the album. He answers thus: “I grew up liking funk but I won’t say this album has funk influence or even my father’s influence. I’ve not listened to music for 18 years. I don’t go out of my way to listen to anything.”

He is searching for a purity in his sound, a uniqueness true to him and to find his soul in the chaos of sound. Listening to others would influence him a lot, he says.

We are done talking. I walk down the stairs, forgetting to replace the chair where I had pulled it from. I turn to carry it back and find Kuti carrying it back for me.

Later that evening, Kuti would again be wrapped in a fog of blue-green-pink disco light. He would sing and entertain a crowd of devoted fans, who had come to forget their sorrows, be inspired and entertained.

He would call “ara ra ra ra” and they will affectionately respond “oro ro ro ro!”

Editor’s note: This article has been modified to reflect that Kuti has been nominated for four Grammys.

Copyright 2025 TheCable. All rights reserved. This material, and other digital content on this website, may not be reproduced, published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or in part without prior express written permission from TheCable.

Follow us on twitter @Thecablestyle

Love this interview and his style of writing. Very interesting. One thing though, Femi has been nominated four times for the Grammy’s

This is a very good, honest and open article. It presents an insight into Femi’s thoughts and beliefs about life and his own life in particular. He has not only become a success in his on right, but proved he is his own person. His vision mirrors that of many of us and has used his music to spread this vision. Femi, well done and keep on keeping on 😊Sinia