BY MICHAEL JIMOH

It is so easy to forget that James Eze was once a journalist, a well-regarded professional who rose to become pioneer Literary Editor of Sunday Sun. Before then he had earned his stripes in Thisday where he wrote features.

By the time he left to work in a bank, some of his editors and close friends thought he had made an appalling professional switch. After all, Eze seemed destined to become a writer, with a book or two to his name.

Why would such a brilliant and promising journalist, they wondered, turn his back on a profession he could hone his skills for one that could possibly deprive him of the quiet contemplation and solitude writers need for their creativity?

Some of them could only guess why. At the time, journalism was not one of the proudest professions anyone could count on, especially financially: some publishers were serial debtors; others paid pittance as salaries while some with a different cast of mind didn’t bother to pay at all. (Confronted once by some of his senior journalists over no salaries, one notorious publisher debtor looked them in the eye and asked: “And why have you not resigned?”)

Perhaps Eze never wanted to be asked a question he can’t proffer any reasonable response to while still in journalism. What to do? Opt out and look elsewhere for plum job opportunities. Thus did he go to Centre Point Bank first, then Fidelity Bank as Head of External Communications. Eze became Public Relations Manager of Airtel Nigeria and thereafter Chief Press Secretary to Governor Willie Obiano of Anambra state, a position he occupies to this day.

These days, Eze functions mostly as an intelligent interpreter of his master’s every wish, as with most CPSs elsewhere, a kind of Jeeves character who decodes his boss’s likely response to an already launched attack or an imminent one. In a state as politically divisive as Anambra, such attacks come as surely as the River Niger is a daily presence in Onitsha.

Sometimes Eze himself, by virtue of his position, is the subject of such barbs. So, it comes as a surprise that, while publicly defending his boss’s policies or views or promoting one all those years, he was also privately preoccupied with poetry, writing good poetry.

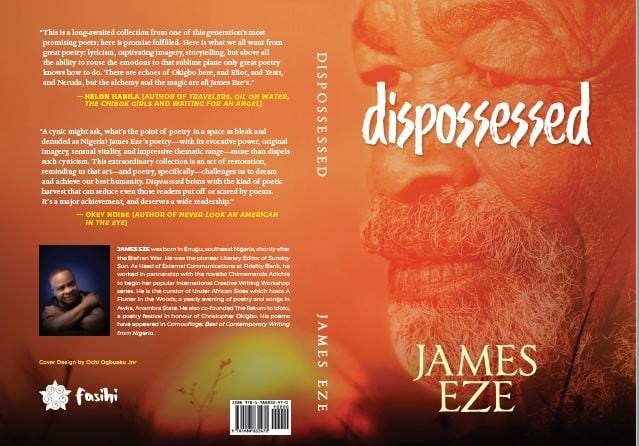

It is all there in this first collection, dispossessed. (By the way, the title of the poem is taken from Irish writer Colum McCann’s famous epigram: “literature can make familiar the unfamiliar, and the unfamiliar is very much about the dispossessed.”)

There collection is helpfully divided into three sections subtitled “innocence,” “transgression” and “atonement.” Section by section, Eze takes readers through the maturing stages of his development as a poet, from the niggling doubt experienced in the first section to the love songs of a maturing mind in the second and then the hardboiled questions he asks in the last.

Everything or subject is fodder for his creative cannon: where he grew up in his younger years, giving readers a taste of the sights and sounds of the towns and cities he lived or worked in. Thus, there are poems written for Anambra, Enugu, Jos, Ozubulu and much more. In most of them, the poet rues their state of decrepitude. Even so, there are fond remembrances of some other places.

In one poem, “when I was a boy,” he writes: “i often ran naked and blind into the rain/ singing songs that even the winds had no breath to whisper into the ears of the trees/ clothed in sheets of the glistening rain/ i immersed myself in the ceremony of innocence/ until mother’s voice cut through the blinding showers to bring me back to earth.”

Counterpointing the verse quoted above and despite such maternal remonstrations, Eze remembers mother’s love nonetheless: “who could question her love served on steamy plates at dinner time? /or her tender touches on my forehead to diagnose a headache.”

That “ceremony of innocence” is the theme that threads much of the poems together in “innocence” made abundantly clear from the epigram preceding it: “the tender cotyledon unfurls to light,” Eze writes, “spreading succulent arms wide to sun and rain.”

In “petals & buds,” the very first poem, Eze craves readers indulgence to come with him on the poetic journey he is about to embark on: “listen with me/ to the joyous laughter of petals/and the suppressed grunts of hesitant buds/ o taste with me/ the wine-song of smiling flowers/ i’m the bee’s seductive drone atop shy buds/ the fragile wings of wooing minstrels have/ awakened the pores of my prescient pollen/ and i sing/ tongue-loosed in time’s ear/amid this bird nest of merry bards.”

With this, Eze has demonstrated that he never really quit writing or writing never really abandoned him. If anything, he has been beavering away all those years, laying verse upon verse each time the muse visited. From the number of poems and range of themes, the muse visited quite often.

In “i am,” for instance, through his very apt metaphors about becoming, Eze compares himself to “the yam tendril in want of sun/ twirling my length on the bark of time…a song in want of an audience.” While seeking an audience, the poet, though a late arrival into the world of poetry, imagines his place among the greats: “here I come/ to the great feast of words/ the late bloomer;/ I come when the table is set/ dinner is redolent with/ the fragrance of great chefs:/ okigbo, Neruda, eliot, pound, yeats…”

The longest poem in the collection is “dispossessed.” It is by far the most wrenching, encapsulating centuries of history from colonialism through independence, sit-tight African rulers to re-colonization and the current state of black people in the world. “we count the/ pockmarks of the last bullets/ on the wall of our bruised pride,” Eze writes of the Biafra experience and its aftermath, “depressed/ we blink away tears/ at the broken promise/ to rehabilitate, reconstruct and reintegrate our fractured lives.”

For the poet, the lost cause of Biafra has resurrected, obviously making a veiled allusion to Nnamdi Kanu’s IPOB: “we drum up hopes of rebirth/ on pirate radio stations abroad/ to induce emotional turmoil for a nation on the cross.”

But the problem of the black man persists to this day which the poet states thus: “self-dispossession is a malignant tumour/ eating up the innards, spreading like rumour/ embracing the world we left nothing of our own/ liberation is a forlorn hope deeply buried in stone/ yielding to cancerous touches encased in a glove/ pray, are we the only colonized people on the globe?/ when will the African sun rise from its roost?/ recovering from an eclipse even a sun might need to boost!”

Dismal as the African situation might be for the poet, he basks with his fellow poets in “the poets’ republic.” Hear Eze: “and god said/ let there be word/ and there was light/ streaming through the window of dawn/ its muted rays strip away the loincloth of ignorance/ to unveil anew the gleaming surface of knowing/ welcome to the poets’ republic/ the eclectic nation of the imagination/ where imageries leap off the tongues of thought/ and words don the mascara of hidden meanings.”

Indeed, for those who have followed his career crossovers closely, writing or serious literature always remained a central focus even while in the bank. At Fidelity, for instance, he bruited the idea of having a Creative Writing Workshop annually for upcoming Nigerian writers, using their already established compatriots like Chimamanda Adichie, Helon Habila as guest teachers. It was a resounding success for all the years the project ran. (A student of one of the workshops, Jowhor Ile, became the first Nigerian to win the Etisalat Prize for African fiction in 2016 with his entry, And After Many Days.)

In August of 2015, six accomplished Nigerian poets converged by the graveside of one of Anambra state’s most famous sons and a grandee of Nigerian poets, Christopher Okigbo at Ojoto-Uno in the Okigbo family compound. It was the first such meeting of bardic minds more than half a century after Okigbo’s death. Obiano’s government, which Eze worked with right from the get go, was only a year in power. It was not hard to see whose idea it was to resurrect Okigbo from the dead through a reading session the late poet would have smilingly approved of.

Eze insists that his relocation to the east helped much in his creativity bursts. “I have been writing poetry for a while,” he said recently in an interview. “But I only began to take myself seriously four years ago. I found the silences that I had wanted for years and the impulse kept coming. That came with my relocation to the south east which has less of the pressure of living in Lagos. So, realistically, it took me four years to layout the foundation and fill it up.”

Eze also describes himself as “intensely passionate about poetry.” Readers cannot but agree after browsing the poems in this collection. Eze unleashes his bardic fury as he draws readers compellingly with his vivid imagination, profundity of thought and feelings, all of that conveyed in a language worthy of a poet at heart. Verse by verse, poem by poem, Eze gives readers a peep into the world he always belonged – a world of poetry.

Having read Eliot, Neruda, Okigbo, Yeats and several others in school and after, it is only too predictable that Eze himself would end up a poet. Predictably, also, Eze doffs his hat in this collection to one or two of the poets he adores. Okigbo is one and there are two poems, “a fistful of kolanuts” and “elegy for the weaverbird” he dedicates to him.

Waxing lyrical with worshipful reverence for Okigbo, Eze begins with the first thus: “i am drunk on lyrics of the broken urn,” continuing in the following lines with the seductive charm of Okigbo’s poetry: “I am afloat on the birdsong of its opium content/ my ablution is complete now/ I can see the naked glory of a nine-headed spirit/ I can hear the eerie laughter in the idoto grove/ my gaze is fixed on the last supper of poets.”

Eze completes his adulation with the next verse: “i approach the table with a fistful of kolanuts.” In many cultures across Africa, presenting kolanuts to a visitor is a sign of goodwill. For Okigbo, his younger colleague does that out of tremendous respect.

In the second, Eze evokes Okigbo’s memory as a troubadour of yore, with a penetrating mind he compares to “the sun’s angry beam/ deflected to this side of the clearing/ to weave canticles/ from fevered mindscapes.”

Not only Okigbo earns Eze’s veneration. Gabriel Okara is another of the grandees of Nigerian poetry he defers to, so aptly captured in the poem “a song for the river nun,” apparently paying obeisance to Okara’s famous ode to the river in Ijaw land, “The Call of The River Nun,” published in 1957. “at the lips of the river nun/ I stand/ to untell century old lies/ from the riverbed -/ voice of the dumbbell/ to sing a dirge to a world with a missing soul,” Eze begins his dedication.

“A song for the river nun” is also a subtle condemnation of the multinational oil companies that have profited at the expense of Ijaws in the Niger Delta. “by the shores of the river nun/ I stand/ to exhume metaphors/ buried with the blood money of multinational firms/ to turn active youths into sleepwalkers.” The repetitive use of “I stand” in the first and second verse and, indeed, in some of the poems is a nod to Okigbo.

One writer gets a hiding, though, from Eze. He is none other than the pipe-in-the-mouth Ken Saro Wiwa for his role and campaign during the civil war. Eze shows his iron fist in a rejoinder titled “re: epitaph for Biafra” and dedicates it to Ken Saro Wiwa. “you took a long drag from your pipe and exhaled/ the memories of erstwhile friends and poets/ claimed by the war they did not ask for/ you let the plume of smoke dull your sense of justice/ you shut the door on right and wrong/ and that’s why you are not my hero.”

The religious fundamentalists also gets a thorough spanking from the poet wherein he portrays in graphic detail fanatics in “ode to the zealot.“ Reading it, you behold the zealot, complete with beards, an angry snarl to the mouth and the ubiquitous sword ready to behead infidels at a moment’s notice. Hear the poet once again: “strung out on the opium of faith/ they sheathe flaming swords/ in fetal hatreds/ to placate a maligned god/ ‘allahuakbar’/ glaze-eyed zealots/ rob our nights of sleep/ the muffled yell of dispossessed placenta/ set el-kanemi’s city ablaze/ it’s the rage of faith miscarried/ they ride our silence to blood-drenched streets/ o the stifled yawn of unfurled petals/ wilted tendrils/ widowed silences.”

It is impossible to assess, one by one, all the poems in this collection. For a first collection, however, dispossessed is a remarkable work heralding a new and unique voice among a rising constellation of literary stars in Nigeria. What it also tells us is that, like some famous banker poets, Eliot et al, they can count their money, do their ledgers or whatever financial records they are entrusted with while not losing sight of what truly is in their heart – poetry.

Copyright 2025 TheCable. All rights reserved. This material, and other digital content on this website, may not be reproduced, published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or in part without prior express written permission from TheCable.

Follow us on twitter @Thecablestyle